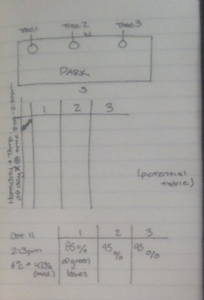

For sampling simulation of Snyder-Middleswarth Site using area-based sampling.

The fastest estimated sampling time was haphazard sampling at 12 hours and 27 minutes, 11 minutes faster than random and 9 minutes faster than systematic sampling.

Eastern Hemlock (common): haphazard – 2.9% ; random – 26.4% ; systematic – 12.3%

Red Maple (common): haphazard – 8.7% ; random – 12.1% ; systematic – 12.5%

Striped Maple (rare): haphazard – 65.7% ; random – 138.3% ; systematic – 8.6%

White Pine (rare); haphazard – 50.0% ; random – 100% ; systematic – 100%

Most accurate sampling strategy for common species (Eastern Hemlock and Red Maple) is haphazard sampling, and the most accurate for rare species (Striped Maple and White Pine) is also haphazard sampling. In this case, haphazard sampling was more accurate compared to random and systematic.

Accuracy, in general, was better with species that are more common, and worse with species that are more rare. The accuracy decreased for rare species as all percentage errors for each of the three sampling techniques increased.

24 sampling points is not a sufficient number of sampling points. With the abundance of each species varying greatly throughout the study area, only having 24 points doesn’t properly represent the number of species. There are a lot of missed species.