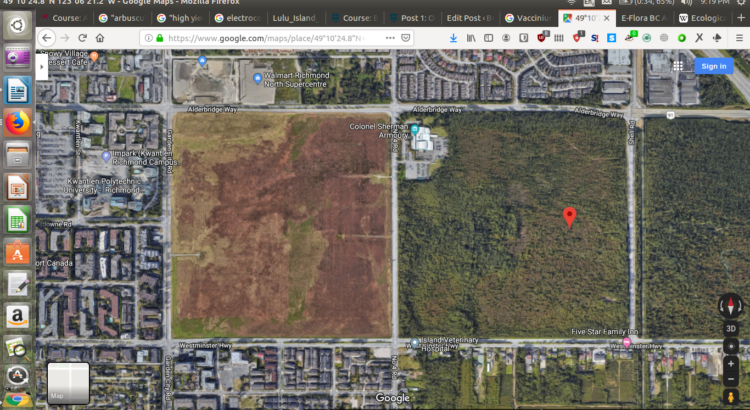

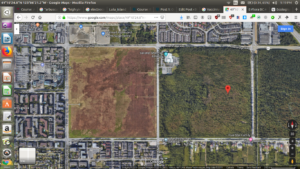

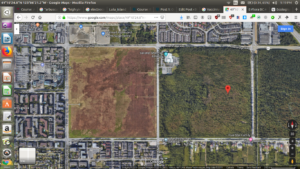

The site that I selected was the peat-lands in the DND Lands in Richmond, BC, between No. 4 Road, Shell Road, and the Westminster Highway. The coordinates for my initial observation point were 49°10’24.8″N 123°06’21.2″W, and my first observations were conducted at 12:15PM, on Sunday 29th of 2019. This particular portion of peat-land does not have an official geographical name; however, it has historically been considered a part of the greater Lulu Island Bog.

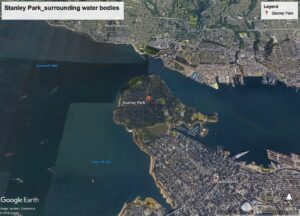

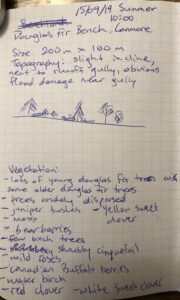

While visiting, the weather was sunny, and 16C. The terrain appears, for all intents and purposes, to be flat, although most peat bogs are known for being either domed, or gently undulating. The particular area that I first explored showed signs of having been subjected to fire in the passed few years. This observation is in line with what I would have expected; in July of last year, I observed the first signs of what was most likely the fire that caused the damage I was currently observing, while I worked at Kwantlen Polytechnic University’s Garden City Land’s farm in 2018, which is located on the parcel of land just west of the DND lands (west of Number 4 Road).

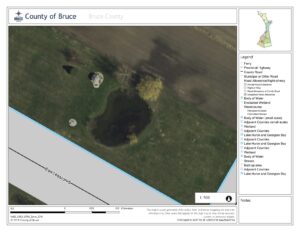

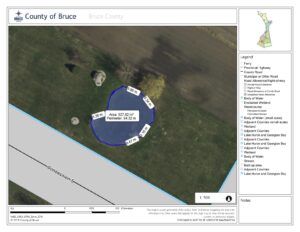

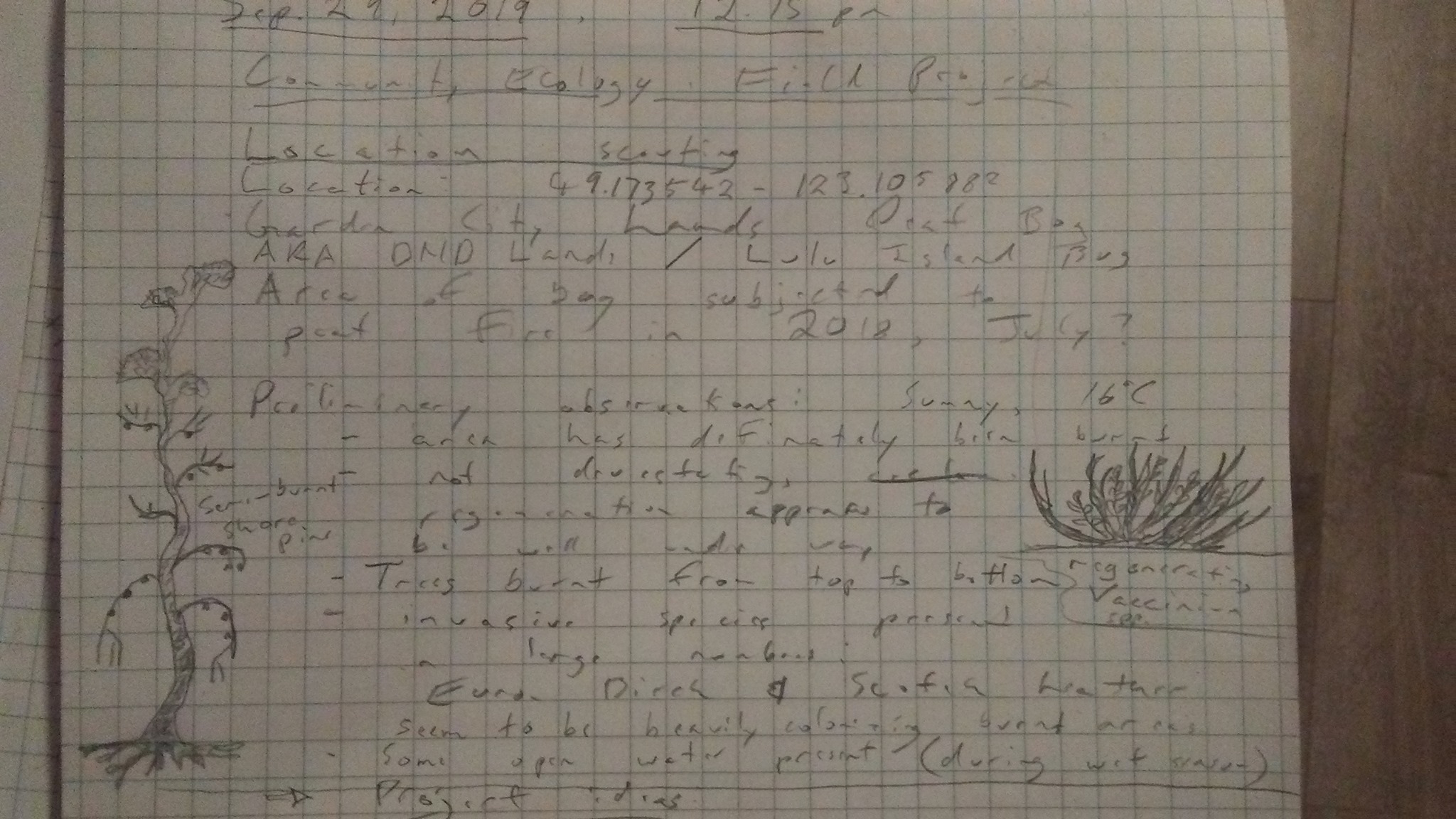

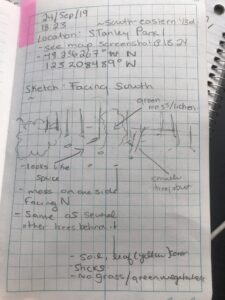

(Aerial view of the DND Lands, inbetween the Garden City Lands, and the Richmond Nature Park. Google Maps.)

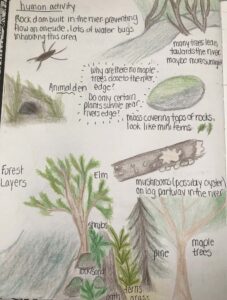

(Above images: Images of burnt over areas observed at initial observation site.)

What struck me about this particular peat-land, besides the blackened Vaccinium spp. shrubs, and shore pines (Pinus contorta var. contorta) (1), was the abundance of invasive Scotch heather, Calluna vulgaris (2), which was regenerating vigorously after only a year since the bog fire took place, along with the proliferation of the seedlings of another alien invasive species, the European birch, or Betula pendula (3). In many places it appeared as if the two species were the primary pioneer species on burnt and exposed sphagnum based peat soils. It also looked as if a lot of the primary fuel for burning may have come from a dense under-story of low shrubs, because the trees and Vaccinium spp. were burnt from the bottom upwards. In a few spots I did notice black pits surrounding larger trees and shrubs that had died from burning, and I suspect that this is where subterranean peat fires may have followed dead roots to the surface, where they may have broke out, and ignited surface fires amongst what appears may have been dense, fine branched, low growing, woody vegetation, most likely Ericacious.

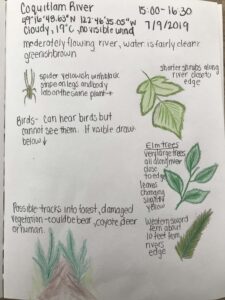

(Above images: Images of vegetation within the bog, clockwise from left to right; Vaccinium spp., cranberry, have yet to confirm the species, young Scotch heather, Calluna vulgaris, colonizing fire effected area, mature C. vulgaris growing with an unknown fungus, northern Labrador tea, Rhododendron tomentosum (4), growing in a cut over firebreak close to burned area, mature C. vulgaris growing beside a trail in part of the bog that was not effected by the fire, and a C. vulgaris seedling growing in the wheel-track of what I’m assuming was a firetruck.)

(Above images: images of effects of fire on the bog, as well as what I suspect are most likely tire tracks left by firefighting vehicles. The second images over from the left is of particular interest, because this may be one of the spots where subterranean fire followed a root to the surface, where it likely ignited surface fires.)

Of interest to me, about this site, is the fact that it contains some of the last Lulu Island bog-lands; also, the fact that I am able to now observe the state of the bog a year after the bog-fire I had previously observed in 2018; and, lastly, the fact that the bog is most likely experiencing changes in floral composition due to the introduction of two new European species.

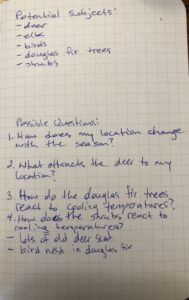

For these reasons, I would like to explore a few interrelated questions:

1) Has the introduction of C. vulgaris led to an increased build up in flammable material in this area?

2) Is the bog being artificially drained, and what effect, if any, is this having on C. vulgaris populations, and the native vegetation?

3) How does C. vulgaris respond to fire?

4) How does the native bog vegetation respond to fire?

The first two questions may be more difficult to ascertain answers to. However, I might be able to deduce hypothetical answers from forensic observations of dead and burned vegetation for question one. Question two may require doing research or conducting interviews with civil engineers in Richmond. The last two questions, on the other hand, may indeed provide testable questions that could provide the basis for an experimental design that focuses on the comparison of alien versus native pioneer species fitness in different locations with variations in the degree of fire damage.

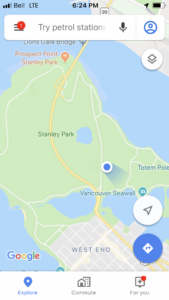

(Above image: field notes of my observations for Sep. 29, at Lulu Island Bog/ DND Lands.)

Citations:

1-4 In Klinkenberg, Brian. (Editor) 2019. E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Plants of British Columbia [eflora.bc.ca]. Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. [Accessed: 02/10/2019 9:14:33 PM